China 2020

CHINA IN THE LIMELIGHT AND THE SHADOWS

China in 2020 Workshop

National Bureau of Asian Research (NBR) and ChinaSource

February 16-17, 2007

In October 1978, I first visited China just before Deng Xiaoping came back to power and the US and China resumed diplomatic relations. Two memories are etched in my mind:

arriving at the Beijing airport in the only plane on the whole field, and after it taxied right up to the only door into the terminal, walking down the stairs from the plane under a bright spotlight and a giant statue of Chairman Mao;

traveling in a car with a driver between two cities in Yunnan for a glimpse of the countryside, when we passed a cross-roads with a dozen farmers seated on the ground with their produce, and the driver whispered to me, “That’s a market, but it’s illegal.”

Would I have predicted the amazing events over the following 13 years -- including the market reforms and SEZs; the 1988 political reform agenda and the 1989 Democracy Movement, followed by June Fourth; and then the collapse of European communism by 1991? So I am kept humble in the face of my task this morning—sharing some thoughts about the next 13 years in China until 2020.

We have learned a lot together in the past 24 hours about major current trends shaping China’s future, with much of the media stressing the “rise of China.” Counter-intuitively—or perhaps just cowardly—I’m going to begin our second day of conversation about China’s future with some reflections on China’s past, motivated by the historian’s perennial hope that we might learn something from history that can guide our future steps. I’ve titled my talk China in the Limelight and the Shadows. While you can read about the limelight in all the articles hyping “the Chinese century,” I want to introduce some of shadows—not all of them negative but rather, legacies of the past that remain in play.

China in the Shadow of Deng Xiaoping

The mindset and timetable that shapes the planning of China’s leaders remains Deng’s seventy-year program of January 1980: Deng reversed Mao Zedong’s utopian priority on class struggle as the means to overcoming China’s weakness and giving Mao a leading role in the Cold War competition between socialism and capitalism. Deng instead put top priority on economic development, to build up a base for later attaining China’s other goals of unification and defense (of China’s interests against “hegemonism”).

Even current government policy is portrayed as adaptation and implementation of Deng’s strategy, which he himself reaffirmed in early 1992. At that time, the beleaguered leadership debated what to do in the wake of post-June Fourth sanctions against China and the collapse of European communism. Deng made sure that China did not “pick up the baton” of leadership in the cause of world communism against the U.S., but stuck to his nationalist agenda.

Goal by 2000 was to quadruple China’s PCI (changed by his advisors to GDP) in 20 years; accomplished early, along with recovery of Hong Kong 1997 and Macau 1999 plus continuing economic integration and political-social assimilation of Far West China.

Goal by 2020 was to quadruple PCI again (also accomplished early); move China into the ranks of “middle income” countries, providing a “comfortable” life (xiaokang) for the Chinese people; all to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the CCP’s founding (1921). This is the timeframe we are considering together, and China again seems to be ahead of schedule—with sustained growth via FDI, a rising middle class, good management of Hong Kong-Macao and patient Taiwan policies, suppression of separatism (new Tibet Railroad), relations with multiple neighboring regions, culminating in talk of a “rising China,” as reflected in basically optimistic scenarios.

Goal by 2050: ensure full unification with Taiwan, Hong Kong, Macau (and Far West); recovery of China’s historical status as a great world civilization … in time to celebrate the 100th anniversary of the founding of the PRC (1949). It is not accidental that Hong Kong and Macau were granted SAR status for “fifty years,” not in perpetuity.

I would note that Deng personally chose Hu Jintao to become successor to Jiang Zemin, who was a compromise candidate reflecting Deng’s loss of face in 1989. So Hu Jintao, as he consolidates power this Fall, will still be operating under the shadow of Deng’s program for strengthening the CCP’s rule through state capitalism and reform of the bureaucracy. The next set of leaders affirmed in 2012 will include those with greater international experience who may be prepared to make greater departures from the CCP’s reform program.

China in the Shadow of Mao Zedong

Some of the challenges facing China are shared by other societies thrust into the intensive globalization underway. The neo-liberal focus on market liberalization has exacerbated inequities in society while weakening the authority of the state and hollowing out redistributive programs for helping the poor. The resulting mixed economy grew in scale but has also fueled opportunities for corruption.

But many of the obstacles to China’s achievement of world-class stature are those typical of former communist countries, which, like China under Mao, pursued a Soviet-style mobilization of all resources to bring about rapid industrialization:

State domination of the economy, media and education works against the goal of world-class innovation required to compete in the global economy

Rapid industrialization left a legacy of environmental devastation and resource inefficiencies

Leninist control by the party over society through monopoly social organizations stifles development of voluntary associations in the Third Sector. (examples: TSPM-CCC and other “patriotic” religious associations, the Communist Youth League, the federations of women’s organizations, trade unions, and charities, and the business and professional associations)

A low trust culture still reflects a zero-sum black and white world view and resort to power struggle tactics, which fuels the pervasive corruption and abuse of bureaucratic power.

China in the Shadow of the Cross

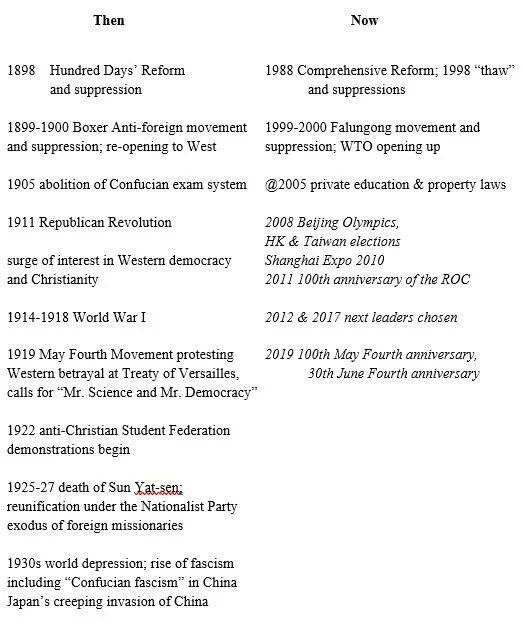

In recent months, I have been reviewing the history of the 1900-1949 period of Chinese and church history for a book project -- writing up the life stories of Chinese Christians in the early modern period. And anticipating our strategy event today, I noticed some very interesting parallels between the 1900-1925 and our contemporary 2000-2025 periods that I want to share with you. Both timeframes were periods of economic globalization, technological advance, social progress and greater openness to Christianity, both in China and elsewhere.

Recently, I noticed that commentator Fareed Zakaria also saw a parallel between the 1920s and the world today -- a prosperous world without a clear political direction. With Britain in decline and America isolationist, “eventually protectionism, nationalism, xenophobia and war engulfed it.” I mention these parallels not to predict the same for us today, but to make the point that much of what happened in China came in response to changes on the outside over which China had little influence (much less control) … changes that took Western missionaries and Chinese Christians by surprise.

Based on China’s modern history, let me offer some of my own predictions toward 2020:

(1) The next five years, 2007 - 2012, will be an important period for shaping the future cultural and political identity of the Chinese people for a post-industrial, post-communist era, as well as relations with the West. Christians need to be players in the cultural realm.

Key dates as catalysts for change (see chart)

(2) Whatever the name of the ruling party -- —Communist or Democratic Socialist or Christian Democratic—in 2020 China will still be a unitary rather than federal state, authoritarian and elitist, with state intervention in the economy and society and some sort of state-endorsed national belief system.

(3) Yet there will also be more openness to allowing diversity and autonomy from the state—for social organizations including faith institutions, for cultural pluralism, and for a confederation with China’s outlying areas.

(4) Between now and 2020, China will experience some level of national social and political turbulence; how severe will depend mainly on the health of the global economy and NE Asian politics. This may include:

rapid growth of political radicalism, fueled by local abuses of power

an undercurrent of anti-foreign nationalism with outbreaks targeting Christians directly or indirectly

Chinese political, even military intervention to protect access to/control over key resources or territorial claims

(5) As has been true in many countries, in the event of a crisis and transition of political power, Christians may be called on to play a role out of proportion to their numbers. . The Evangelical Protestant culture of voluntary association and active citizenship tends to equip Christians to play a democratizing role.

(6) Finally, let me suggest the Singapore Model as the best-case scenario for China in 2020. On one hand, we can pray against the worst-case scenarios, and on the other, we can’t expect that China will become the “Third Republic” the dissidents in exile are working for—a federal, constitutionalist, liberal democratic country with moderate nationalism. But it might look more and more like Singapore.

In fact, Deng’s long-term program, which turned away from the European communist model, was an attempt to replicate the economic takeoff that allowed Asia’s “tiger” economies to break through the barrier between underdeveloped and developed worlds, and by closing the gap to reincorporate Taiwan and Hong Kong-Macau. Jiang Zemin in turn was enamored of the Singapore model under Lee Kuan Yew’s benevolent autocracy. He even invited the Singapore government to set up a special industrial zone near Suzhou to apply all their economic and political expertise … which died an unheralded death after local officials siphoned off all the FDI for a parallel zone under their control.

The public face of the model = state capitalism and mercantilism, authoritarian government, and “Asian values” (a term more acceptable than “Confucian” in Asia’s multi-ethnic context) imparted through “moral education” in the schools to complement the growth of an “R&D Culture.” This model emerged beginning in the 1970s with a new focus on how to position Singapore to compete successfully in the new global economy. Since then, the government has been on a treadmill of new policy initiatives required to keep up with the pace of global change. More responsive governance has been required to maintain the PAP’s monopoly on power. Draconian anti-corruption laws, and public clean-up campaigns are seen as necessary to attract FDI.

A number of these themes are echoed in China under Hu Jintao:

populist slogans calling on officials to serve the public benefit

a strategy of balanced development to stem growing inequality

slogans calling for a “green, scientific, and people’s Olympics”

calls for a harmonious society

anti-corruption campaigns and Hu’s moralistic “8 dos and don’ts”

creating “world class” universities to fuel innovation for high-tech industry

Government sponsored Confucius Institutes around the world to spread Chinese “soft power.”

A recent CCTV special on the “rise of great powers” highlighted accomplishments in science and technology rather than social-political institutions or moral values. Apparently, “Chinese style socialism” is now nationalism plus S & T plus Confucian values.

Behind the scenes, however, Singapore’s success actually reflects a very strong Evangelical Christian influence:

40% of Parliamentarians are Christian (in a society less than 10% Christian)

Dr. Tony Tan, former Deputy Prime Minister and Defense Minister, was expected/asked to become Prime Minister in 2005, but instead runs the National Research Foundation as an archetypal “Christian Confucian,” according to friends in Singapore.

They reflect an expanding and influential Asian Christian network that includes Hong Kong & Taiwan Christians. One researcher hopefully predicts that the Asian Christian use of the Internet will realign the regional configuration of power, wealth and organization.

Looking to the future in light of the past, what are some key issues for China ministry?

(1) Political and economic trends worldwide greatly affect China.

In the 1920s and 1930s, China missionaries and Chinese Christians were not prepared for the swing toward radical politics and military violence, as warlords battled for territory and the elite turned away from the “Christian” West in disappointment over its inaction in the face of Japanese aggression.

Dependency on mission funds, policy direction and institutional management made Chinese Christians vulnerable to criticism and suspicion that they were “traitors” rather than patriots. They had neither the confidence nor the vision to transform society.

(2) Underlying currents of nationalism, ambivalence toward the West, and anti-Christian biases will become a greater problem for two reasons:

Hyper-nationalism is emerging among today’s youth, who are finding their personal identity in the cause of a “rising China.” These pampered only children, unlike their parents, have been isolated from China’s internal poverty and repression, growing up in the bubble of coastal affluence.

Populist and socialist concerns are aroused by the neo-liberal approach to globalization, which fuels the perception that it fosters growing inequities and corruption. Some Chinese will be joining the world-wide anti-Globalization movement. To what extent are Christian institutions identified with the winners or with the losers in the global market?

It is important to separate out biblical principles from the “American way” and move faster to get out of the driver’s seat and focus our efforts on supporting and training indigenous leaders for indigenous projects. There is an urgent need for mainland Chinese Christians now overseas to get leadership EXPERIENCE in all fields.

We need to work closely with the Asian Christian identity and networks. In God’s providence, much of the early modern educated Chinese Christian middle class ended up overseas and is now shaping the growth of the church in China.

(3) The whole cultural realm is our field to plow. We can’t just focus on “religious work” in China—Evangelism and Discipleship, church-planting, pastoral training—assuming that this will automatically influence society in a positive direction. We need to also be thinking: Who is the competition? Who are our allies?

The Chinese church as an institution is likely to remain vulnerable and marginalized, even as believers and their families and networks grow in influence.

Several reasons inhibit the church’s influence: the old-fashioned official church; suppression of the house church; the intellectual elite’s aversion to church. Exploration of new models for the church are much needed.

If we stop to analyzse who really are the change agents preparing the way or seeding the gospel in urban China, we will discover that they actually include more actors outside than inside “religious” channels. [Foreigners including Overseas Chinese on campus or in business in China, mainland Chinese Christians now overseas (as they and relatives come and go), Chinese scholars doing research and translation of Christian materials in secular channels, Chinese Christian Internet and radio.]

As we work in the context of cultural globalization, we will realize the importance of the AFFECTIVE ties of RELATIONSHIPS across borders. When we apply business models to doing or funding ministry, we may gain accountability and efficiency, but may also be shifting the orientation to goal achievement and impersonal relations.

CONCLUSION

Christians in China similarly are called to be Salt and Light in the larger society, which is suffering from such spiritual poverty in the midst of material prosperity. “Chinese people want a better life but feel lost in a cold, utilitarian society.” Corruption is endemic—e.g. “blackmail journalism.”… How do we help our brothers and sisters address this need?

The most important task would be to pray for continuing miracles of God’s mercy, on the assumption—as a friend of mine put it, that God has preserved China from “falling off the cliff” for His purposes.We can all join the “One million praying for China by Sept. ‘07” movement (see www.prayforchina.com), and pray most immediately for God to raise up godly leaders through the promotions underway for the next five-year Party and People’s Congresses this fall and next spring, and then for the growth of the Kingdom through the Olympics events.