The Unexpected Christian Century: Book Review Part I

Scott W. Sunquist, The Unexpected Christian Century; The Reversal and Transformation of Global Christianity, 1900-2000. Grand Rapids, MI: Baker Academic, 2005.

A book summary, with special focus on Chinese Christianity

Noted historian on the subject of World Christianity, Scott Sunquist has given us another outstanding volume. The author of Understanding Christian Mission (reviewed in these pages here) and co-author of History of the World Christian Movement, Vols. I & II, he possesses both a wide knowledge of the Christian movement’s history as a whole and a comprehensive grasp of Christian missions in all its dimensions.

The Unexpected Christian Century follows a format that departs from the region-by-region approach of the History of the World Christian Movement series. That is because, “in looking at the twentieth century we can no longer talk about the development of Christianity in South Asia as separate from the development of Christianity in North America or in West Africa. With globalization coming to flower in the twentieth century, Christian movements like Pentecostalism occurred almost simultaneously in China, South Korea, northeast India, Chile, California, and Scandinavia. It is more honest to talk about global themes than about geographic regions” (xxiii).

After opening with a brief history of World Christianity from the Gilded Age to the Great War, this book therefore discusses five grand themes:

Christian Lives: Practices and Piety

Politics and Persecution: How Global Politics Shaped Christianity

Confessional Families: Diverse Confessions, Diverse Fates

On the Move: Christianity and Migration

One Way among Others: Christianity and the World’s Religions

An Epilogue: Future Hope and the Presence of the Past concludes the volume.

The twentieth century surprised “the religionists, the historians, and the politicians.” It was one of the “three great transformations in Christianity in two thousand years.” The first took place in the fourth century, when Christianity “moved from being a persecuted minority to being a favored faith.” This changed everything. The second transformation occurred in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, when “Christianity broke out of its small enclaves of Western Europe, South India and Ethiopia and became a truly worldwide religion… The third great transformation took place in the twentieth century, a great reversal…in that the majority of Christians – or the global center – moved from the North Atlantic to the Southern Hemisphere and Asia,” and “in that Christianity moved from being centered in Christian nations to being centered in non-Christian nations. Christendom, that remarkable condition of churches supporting states and states supporting Christianity, died” (xvi-xvii).

A key aspect of this was “the globalization of the faith,” in which “Christianity participated in (we might say was one of the pioneer movements in) globalization” (xvii). Christians are found everywhere, but so are Muslims, Buddhists, and Hindus. The spread of Christianity came about as a result of various causes, including “the spread of Pentecostalism…[which] forced migrations of people, ongoing missionary work, and the advances in communication and transportation. As a result, it is not really possible to talk about Christianity by region or continent because so many of the themes are global” (xviii).

Hence the structure of this book.

Introduction: From Jesus to the End of Christendom

The Introduction tells the story of the first nineteen hundred years of Christianity, “noting the major shifts and turns that took place until we end up with Christianity of the imperial age, or the Gilded Age, when almost all Christians lived in the West… This introduction is about how Christianity, an Asian religion, became a European and Euro-American religion. This book is about how the twentieth century, actually just the latter half of the twentieth century, changed all that” (1).

We learn that the earliest Christian was a movement, the Jesus Movement, that relied on the power of the Holy Spirit rather than earthly powers. Then, in the fourth century, a few rulers, including Constantine, the emperor of the Roman Empire accepted this new faith. “The results transformed the new religion.” From then on “the early spread of Christianity depended to a great extent upon the conversion of rulers” (2).

Lest we misunderstand that fact, Sunquist hastens to emphasize, as he does throughout, that “from the beginning, Christianity has had a missionary impulse” (3). Believers just had to tell others the Good News.

As Christianity became a multi-national, multi-cultural religion, it had to find ways to express a universal faith in local contexts. Sunquist believes that the ecumenical creeds represented an attempt to “express the meaning of Christ in ancient philosophic concepts” (3). I’m not sure about that. Yes, some key terms, like “substance” and “person” were taken from existing philosophical vocabulary, but they were chosen in response to questionable explanations of the biblical language about Jesus and his relationship to God the Father and to the Holy Spirit. Though times and terminologies have changed, up to the present Christians have not been able to expound the core elements of the faith any better.

Still, it is true that the perennial challenge for missionaries and their converts has been so to “translate” the Bible’s message into local languages and cultures as to remain faithful to the Gospel while being understood by new adherents.

Christians in different lands had a great impulse for unity; they knew that they belonged to the same spiritual family. Thus, the emergence of the Great Church through the Creeds.

In time, “the impulse for unity often became a need for uniformity,” as state-backed church leaders imposed religious conformity upon all the people in their realms (4). This sad feature of Christianity persisted in Europe and other places until the American Constitution created a new model: the separation of church and state. The story of Christianity until recently, contains far too many tales of persecution of “heretics” or “unbelievers” by “Christians.”

One way to resist state-sanctioned ecclesiastical control was to form monastic societies. These new organizations spearheaded the expansion of Christianity into new regions for many centuries afterward. In time, however, they often became institutionalized themselves. In the sixteenth century, two great transformations took place, by which “Christianity developed four major families from two, and Christianity became a world religion” (7). “Spiritual” and “Reformation” church bodies were created, shattering the unity of Western Europe.

The second transformation was that, through the explorations and conquests of Roman Catholic powers, Christianity broke out of Western Europe into Africa, Latin America, India, and Asia. “The methods of evangelization in this early period were medieval (convert or else!), and yet Latin American was closely evangelized” and outposts of Roman Catholicism were founded in Africa and Asia (10).

Christian Mission Recovered: Seventeenth through Nineteenth Centuries

This was the great period of missionary work around the world. Sunquist highly praises the Jesuits, who spearheaded the Roman Catholic movement, for their sensitivity to local cultures and for seeking to “present Christian faith in local forms and language” (11). Their methods have had strong critics, both Roman Catholic and Protestant, however.

Often following in the footsteps of Roman Catholics, Protestants later created their equivalent, the missionary societies that took the Gospel to Africa, Asia, India, the Middle East, and Oceania. They, too, were concerned for local cultures, “especially learning language,” and they made translation of the Bible their first priority. Almost from the first, medicine and education became “the two great and powerful tools in the toolbox of Protestant missions” (13).

Christianity, Modernity, and Missions in the Nineteenth Century

Roman Catholic, and to a lesser degree, Protestant missions often went hand-in-hand with promotion of Western political power and culture. Towards the end of the century, Protestants became divided between “liberal,” or ‘modernist” and “fundamentalist” camps. These divisions persist today.

Chapter 1 - World Christianity: The Gilded Age through the War

After this foundational introduction, Sunquist describes what global Christianity looked like in 1900. At the turn of the century Christians confidently believed that, with the expansion of the reach of “Christian” empires and the opening of global markets, Christianity would spread, too. “It has always been a problem to identify Christian rulers with the king of kings or Christian nations with the kingdom of God” (16).

This chapter look at “dynamics at play in Christianity around the turn of the century,” and “the Christian presence globally during the transition from the Gilded Age (1870s to 1900) through the Great War [World War I]” (16). The War, in which “Christian” nations slaughtered each other, shattered confidence in Western civilization in general and, for some, Christianity as well. The influenza pandemic killed fifty million people. The Great Depression devastated Western economies and affected the world. Germany re-armed and another war loomed.

Meanwhile, the center of political, military, and economic power was shifting from Western Europe, especially Great Britain, to the United States. American big business funded big missions and big ecumenical conferences, full of confidence in a big movement that would soon sweep the whole world. Some missionaries brought the old gospel of salvation by grace through faith in Christ, but others touted modern science, economics, education, medicine, and progress in general.

While all this was happening, “non-Western church leaders were quite aware that Western Christianity was struggling to rise above its own materialism and nationalisms” (17). Indeed, during this period, “The main story would be the spreading decay of this Christianity as the West…and the remarkable vitality of Christianity from the margins” (18).

“One of the greatest themes of this period of transition in the early twentieth century was the relationship between Christian missions and colonialism” (19). This very “delicate” relationship was becoming the main issue. Colonials experiences by native peoples both helped and hindered the growth of Christianity. “Oppression, more than colonialism or imperialism, seems to be the most important factor” (19).

An even more important question, however, is “about the intent of the colonial powers and the intent of the missionary societies” (20). Christianity’s role “was not unqualified support for the colonial agenda” (21). The situations were complex and diverse, but, generally, “Christian mission planted the seeds for the survival and revival of Christianity in non-Western lands, and at the same time planted the seeds of future movements of liberation in Asia and Africa” (23). Translation of the Bible stimulated both Christianity and local languages and religions; Christian education, especially higher education by liberal missionaries, fueled the revolutionary nationalist movements that later threw off the colonial yoke.

Sunquist highlights the 1920 Edinburgh Missionary Conference as “the transition of Western Christianity from spiritual movement to modern business affair.” It also “reminds us how divided Christianity had become since the sixteenth century” (24). “Third, the conference marks how central the missionary movement had become to Western cultures,” with thousands attending, journalists reporting, and politicians supporting the meeting (25).

The Conference also showed “the internal struggle that Western missionaries and their missions had to give up leadership of their overseas institutions” to local Christians, only a tiny number of whom were invited to the gathering (26).

For the last time, Protestants at this meeting all agreed that Christian mission “was rooted in the atoning death and resurrection of Jesus Christ for all peoples,” and the mandate to carry this saving message to all nations (26).

Finally, the conference marked the “beginning of one of the major themes of Christianity in the twentieth century: the ecumenical movement for global Christian unity”; a continuation committee set in motion plans that would lead to the World Council of Churches (27).

Within a year, however, the theological consensus of Edinburgh was breaking down, as major church leaders began to hold the view that Christianity must not only study and respect other religions, but also learn from them and perhaps even incorporate some of their teachings into the faith.

In America, Christians were divided between those who held to the traditional message and those who thought that the old faith must accommodate itself to the so-called “findings” of modern science. The Bible came under criticisms as old-fashioned and full of errors. The government stepped in, and insisted that Christianity must no longer be the central assumption of public education. Another question was how the Gospel was to be expressed in an increasingly secular society.

As Western Christianity lost vitality, its struggles impacted believers in Africa, Asia, and elsewhere. In China, some followed modernist teachings, while others believed and boldly proclaimed the ancient Gospel.

Pentecostalism also brought vitality to Christianity in other nations. Immigration led to the strengthening of movements like Eastern Orthodoxy in North America.

Meanwhile, major transformations of Christianity were taking place outside the West. In China, Jing Dianying started a Pentecostal movement. The period saw the rising influence of Wang Mingdao, John Sung, Watchman Nee, David Yang, and Marcus Cheng, all of whom “stressed repentance, conversion, holiness, doctrine, and discipleship. They were the vanguard of a great revival that swept through the Chinese churches of the late 1920s and 1930s. Evangelical and antiliberal, they decried the leadership of modernists and liberals in their churches” (33, quoting Harvey, Acquainted with Grief, 24).

In this chapter and elsewhere, Sunquist pays detailed attention to the many African independent churches that became a continental movement parallel to the campaign for national independence. In Latin America, political movements influenced by Marxism changed the political landscape, including the Mexican revolution that greatly reduced the influence of Roman Catholicism. As in North America, “newer immigrants were arriving…bringing newer forms of Christianity” (34).

All over, the new ideologies “challenged the place of the church, as well as the very existence of God. The Christian church had never faced such a formidable and influential global idea in nineteen centuries.” At the same time, “especially for the optimistic Americans, it was a time of great opportunity and hope. Christian empires were extending their influence, and churches, schools, and even Christian colleges were being built in the heartland of Hindu, Muslim, and Buddhist territories… Overall the assessment was that the greatest opportunities for Western Christianity were ahead and that the Great Century that was coming to a close was opening the door for an even greater century. What actually happened, no one predicted. Western Christian hope was hope misplaced” (35).

Having introduced the book’s first chapters, which introduce the “unexpected twentieth century” itself, I shall narrow the focus of the rest of this review. Since these pages highlight Chinese Christianity, I shall only discuss what Sunquist says about that in the treatment of his five major themes.

Chapter 2 - Christian Lives: Practices and Piety

“Christianity from the beginning has been the story of individuals in communities living out the life of Christ in and for particular contexts. It is the story of everyday people placing their lives, hopes, and decisions in the light of Jesus Christ and the church. And so we now turn to examine some twentieth century followers of Jesus, particularly those who have had a great impact on the shaping of Christianity across the globe” (37).

To represent China, Sunquist first discusses the great evangelist John Sung (Song Shangjie, 1901-44), “whose impact was felt globally, although only among Chinese speakers” (50). He received a PhD in Chemistry at Ohio State University, then briefly attended Union Theological Seminary. During an intense emotional and spiritual crisis, he experienced God’s saving love.

“After returning to China, the Bible would be his only textbook, and he would retain a great distrust of Western theologians and missionaries. Sung’s significance, in term of his ministry and his reputation, comes from his strong commitments to basic issues of Christian lifestyle and Christian teaching. He lived very simply, eating mostly rice, vegetables, and teach, with very little meat. He wore a simple white Chinese cotton outfit and prayed for hours every day for specific people he had met in his travels…

“In his travels he spoke clearly about repentance from sin and the need to reshape lives in conformity to that of Jesus Christ” (51).

Tens of thousands responded to his messages with lasting repentance and trust in Christ, and probably thousands received healing through his prayers. Wherever he spoke, “he would form evangelistic bands, who were to study the Bible together, pray for the salvation of others, and then go out to evangelized their communities” (51).

“Sung represents a very strong stream of Chinese Christianity that has a Confucian concern for right behavior, a Chinese concern for independence from the West, and a ‘Bible only’ approach to theology” (52). I mostly agree with that assessment, except that Sung’s exhortations to a holy life were supported by reference to Scripture.

Watchman Nee (Ni Tosheng, 1903-72) is one of the best-known Chinese Christians in the West, largely because many of his sermons were transcribed and then translated into English as books – more than 60 of them. Though heavily influenced by British “Keswick” teaching, Nee’s version of spirituality “would in the end look more Confucian than Anglo-Christian” (52). Nee, Wang Mingdao, and other independent Chinese Christian leaders, “spoke against what they saw as the theological compromises of Christians such as Wu Yaozong (Y.T. Wu), graduate of Union Theological Seminary in New York and the first chairman of the Three-Self Patriotic Movement (TSPM)” that was the only state-sanctioned Protestant body.

He established what became a denomination, though he decried Western denominationalism. Arrested in 1952, he spent the last twenty years of his life in prison.

“His loyalty to his flock, his writings, his deep spiritual cultivation, and finally his suffering have made him a very influential Christian leader globally. Most of Nee’s churches did not join the TSPM and became, and continue to be to the present day, one of the major streams of the underground church movement in China…

“In contrast to these Chinese evangelists and spiritual leaders are those Chinese Christians who accepted Western theological thought and political theory and developed theology and church leadership more publicly” (53).

To be more precise, these men accepted Western liberal theology. They included Y.T. Wu and Anglican Bishop Ding Guangxun (K.H. Ting, 1915-2012). He “personally, but not publicly supported the Anglo-Catholic Marxists” (54).

After several years in the West, he returned to China in 1951 to head up the “government-recognized China Christian Council (CCC). As elsewhere in this book, Sunquist believes that “it is not our responsibility here to make judgments,” but he does note that Ting was instrumental in getting Protestant churches opened after the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976) and that he “argued for greater religious freedom while a member of the National People’s Congress and at the Chinese People’s political Consultative Conference” (54). (He does not mention Ting’s leadership of the TSPM in joining with government forces to persecute unregistered Protestants.) Sunquist correctly says that “Ting was more of a political theologian, thinking and writing about how the church can exist and participate in society” (54).

He acknowledges that “Ting’s positions were strongly criticized by many Christians overseas and by Chinese Christians who suffered during the first three decades of Communism,” but goes on to emphasize “the great impact he has had on Chinese Christianity and, globally, on how Christian theologians think about Christian life in society” (54).

Chapter 3 - Politics and Persecution: How Global Politics Shaped Christianity

“The simple confession of Jesus Christ as Lord, coupled with the obedience such a confession requires, led to Christians being persecuted throughout the century and around the world… [T]he twentieth century was the century of the greatest persecution and martyrdom for Christians” (78).

After presenting a list from a variety of countries and contexts, he observes that “nationalism and national ideologies (dictatorial fascism and Communist atheism) are the major causes.” In looking at “global political change, persecution, and Christian life,” Sunquist states: “Key to this change was that the world map was transformed between 1946 and 1991, which meant that the global ‘Christian’ empires dissolved and Christianity lost its privileged position” (79).

During the last four decades of the twentieth century, the center of Christianity shifted dramatically from the West (Atlantic world) to Africa, Asia, and Lain America (the ‘non-West,’ for shorthand). “In the West, Christianity declined largely as the result of “intellectual movements from the Enlightenment” (79). Political changes served as the main catalyst for the faith’s growth in Asia, where “Christianity, detached from colonialism and the supports of Western missions, stood on its own and became rooted in local social and cultural realities” (79).

With “about 4,300 people…leaving the church in Europe and North America every day, and not being replaced,” increases in the rest of the world, meant that “at the end of the first decade of the twenty-first century, Christian was nearly two-thirds a non-Western…western religion” (81).

“Another great shift has been from Protestantism to the newer Spiritual churches (Pentecostal, Free Churches, and indigenous churches)… First, many of the indigenous churches…communicate the message in patterns that are more culturally appropriate for their neighbors… Second, most of the missionary work at the end of the twentieth century was done within continents by local, indigenous Christians” (82).

Wars played a huge role in this shift as “Western nations, mostly identified as ‘Christian,’ were also responsible for some of the greatest violence… World War II…devastated Western Christianity. Christians were killing other Christians for what had become a higher loyalty: nation” (83). In Japan, it was predominantly “Christian” America that dropped atomic bombs, while in Germany most “Christians” supported Hitler.

Regional conflicts also had a big impact on Christianity. “First, in some cases Christianity survives and then thrives on the other side of war,” as in Korea (85). “The same could be said of the Chinese War of Liberation (or Civil War)… On the other side of the war and persecution, the Chinese church grew dramatically” (85).

“Second, at times war decimates the Christian community and cuts of the life source of the church,” as it did in the Middle East and Spain. “Third, wars have created Christian refugees, who have then diversified Christianity in the West… Finally, when wars end, there is always a new order… The two great determinants of how Christianity survives are the overall health of Christianity before a war and the resulting social order after a war” (86).

China

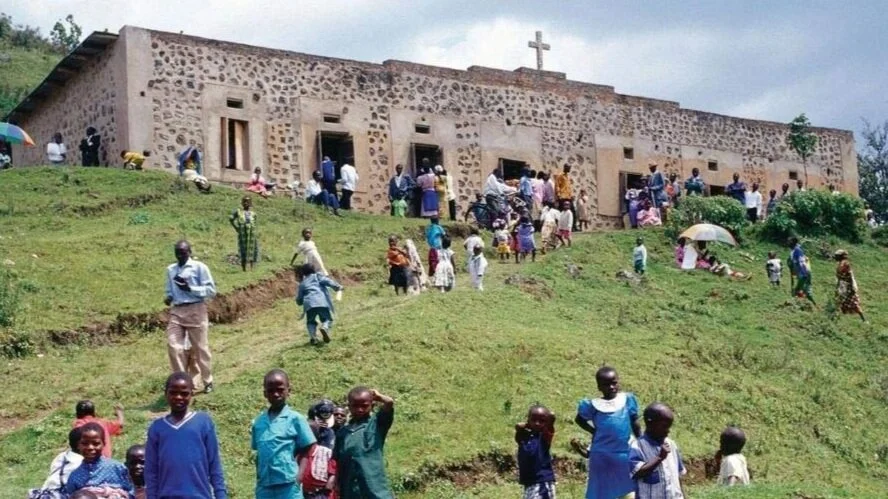

Since 1949, “the growth rate [was] greater in two generations than in any single nation in Christian history” (81). The church suffered greatly under Mao and his successors, but the result was unprecedented growth, both there and in nearby countries, where expelled missionaries and migrating believers spread the gospel.

The author correctly points out that it was mostly those “who had come from Anglican, Episcopal, Congregational, and some Presbyterian and Methodist missions and churches, as well as the YMCA and the World Christian Student Movement,” who “sought ways to work with the CCP” (Chinese Communist Party) and supported the state-sponsored (and controlled) Three-Self Patriotic Movement (TSPM) (90). Those who resisted the TSPM “came mostly from Baptist churches, independent churches (including indigenous churches), and China Inland Mission churches.”

Sunquist’s conclusion is striking:

“Left on their own – cut off from foreign money, leadership, or training – Chinese Christian found ways to survive and pass on the faith… The difficult experience of the Chinese churches under Mao’s form of Communism did more to promote Chinese Christianity than 140 years of Protestant missions. Interestingly, both the missionary work and the Communist persecution were necessary” (90).

We can confidently expect the same outcome from the new wave of persecution under the current Communist regime.

(To Be Continued)